Book Review: A History of Manhyia Palace Museum: Inaugural and Other Objects By Ivor Agyeman-Duah

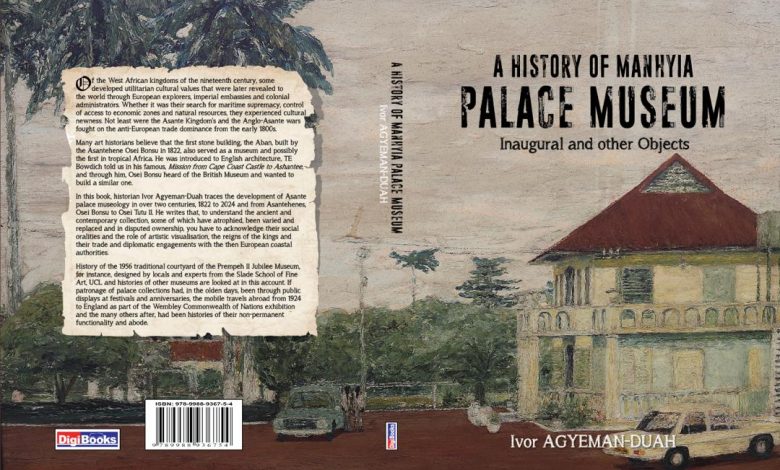

A History of Manhyia Palace Museum: Inaugural and Other Objects by Ivor Agyeman-Duah tackles Asante art history, and how this intersects with the making, decline and remaking of the Asante empire itself, with glimpses of the psychology of Asante kings and queen-mothers who directed these political events.

By focusing on the inaugural objects which have been returned to Manhyia Palace Museum by the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum, the book also introduces us to the politics of art restitution. Agyeman-Duah observes: “If the initial idea of reparation was more about compensation for what was taken from Africa, particularly the human capital through slavery, restitution, and what became restitution objects, were the visible and tangible materials which can be rightfully returned to their owners.” (p.174-175)

The book runs to 224 pages, with 9 chapters including an introduction and epilogue, and over fifty images. Gus Casley-Hayford, Director of V&A Museum East, provides an insightful foreword.

I want to focus on three cross-cutting themes that run through the chapters and help a reader to understand the wider issues of art, empire(s) and restitution.

1st theme

The first theme is Asante art itself. Who produces it? How is it produced? Who owns it? What functions does it serve for royals and lay people, and for friends and adversaries of Asante? Through images and text, we see several art objects: wooden stools, gold busts, velvet umbrellas, silk textiles, musical instruments, paintings, proverbs and poetry.

We see the artists who produce the art. The Dwumfour (“designers of royal regalia – based at Manhyia Palace – who train as apprentices before becoming masters” (p.102)); the artists in famous villages like Bonwire and Pankorono who produce kente and adinkra; “commercial gold, silver and brass smiths” (p.105); contemporary artists who paint portraits and sculpt busts and effigies of kings and queen mothers; and also, foreign artists commissioned to capture Asante royal life and village life in real time for foreign consumption.

We see how the structure and functions of art change over time, through cultural exchanges, and strategic borrowings. We also see the long history of a museum idea by Asante royals. In the 1770s, the 4th Asantehene, Osei Kwadwo, was interested in building “an elegant or extravagant palace to be adorned with gold and to keep treasures” (p.69). He “built the Bremang village (about five miles from Kumasi) and a long mausoleum with galleries, the architecture of which he supervised and which has since become the resting place of Asante kings (p. 69).

His successor, Asantehene Osei Bonsu pursued this vision, and built the Aban (meaning government in Asante Twi) in 1822. The Aban was described as a museum “where the art treasures of the monarchy were stored” (p. 72), or “a Palace of Culture” (p.72) or a storage space for the many gifts bestowed to the court from foreign dignitaries.

In the 1950s, when the Asante Cultural Centre was established by the Oxbridge educated anthropologist Alex Atta Yaw Kyerematen, the Prempeh II Jubilee Museum became a centre piece in this space. This is where selected royal objects and regalia were kept and displayed before Manhyia Palace Museum was inaugurated in 1995.

These iterations of the royal museum have functioned to house works of royal art. But the museum has also existed outside four walls, its objects weaving through public events. “It is easier” Agyeman-Duah notes, “to see some of these objects during festivals like Awukudae, Akwasidae, Adaekese and even the rare ones like Odwira, than in any museum or private storage space where those in charge have them.” (p. 112)

Furthermore, at these public events – which Agyeman-Duah describes, aptly, as “fleeting or mobile museums” (p.107) – the power dynamics between rulers and subjects come to the fore. “When the Asantehene appeared in public in full regalia, displaying all state paraphernalia with thousands of his subjects in jubilation drumming and dancing, this provided an opportunity of assuring themselves that he had kept intact the state treasures he had inherited on their behalf.” (p.144-145)

2nd theme

The second theme is encounters between Asante and the British. It is important to note that Agyeman-Duah signposts encounters between Asante people and other European groups, such as the Portuguese, Dutch, French, Danes and Swedes. For example, he notes, citing Kwesi Anquandah, that by 1560 “the Portuguese trade alone had made over ten percent of global gold supplies, the bulk of which had come from Ashanti and the forest country.” (p.68). However, the major focus of the book is on Asante-British encounters on Asante soil or on British soil; and these range between the pleasant and the violent.

In the early 1800s, Asantehene Osei Bonsu’s “interest in understanding Englishness” (p. 68) coincided with the visit of Thomas E. Bowdich, a young Englishman who had been sent by the African Company of Merchants to Kumasi to survey Asante life in full as a conduit to establishing trade relations. Osei Bonsu (then in his thirties) and Bowdich (in his twenties) became friends and frequently discussed architecture and the arts. Bowdich created colourful illustrations of Asante royal life and events, was gifted art by Osei Bonsu, acquired art of his own and, much later, donated his acquisitions to British museums.

In 1874, Osei Bonsu’s Aban was invaded and looted by British soldiers, led by Sir Garnet Wolseley and Robert Baden-Powell (founder of the Scout Movement), and assisted by African troops and the chief of Elmina. This operation was officially approved by the British government, following much debate in the House of Commons. In one of the many fascinating historical nuggets Agyeman-Duah unearths from eclectic sources, Henry Brackenbury, Wolseley’s military secretary and army general, paints a tragicomic English scene of looting by candlelight: “Candles were scarce at Coomasie, and only four were available for the search, of which economy forbade that more than two should be alight at a time. By the light of these two candles, the search began.” (p.129)

The day after the looting, Wolseley and his forces set fire to the Aban and surrounding houses, igniting a three-day battle between British and Asante soldiers which cost 4,000 Asante lives. The loot, comprising royal artefacts – such as gold masks, gold necklaces and bracelets, carved stools mounted in silver, knives set in gold and silver – was auctioned off in Cape Coast. European traders, soldiers and prominent Africans bought some objects and resold them at higher prices. Unsold objects were gone to the Crown Jeweller in England. The provenance of many of the stolen objects in British and American museums can be traced to this singular event, which has been named the Sagrenti war – Sagrenti being a Twi pronunciation of Sir Garnett.

A century after Bowdich’s visit, other British cultural explorers followed. Anthropologists like Robert Sutherland (RS) Rattray and Meyer Fortes, and folklorists like Peggy Appiah conducted meticulous examinations of cultural traditions, religious rituals and village life for scholarly and/or political purposes. In 1924, a grand exhibition was held in Wembley, London, to showcase the Commonwealth of Nations. RS Rattray organised a Gold Coast pavilion, which had an Asante village as its centre piece. He took thirty people from Kumasi to Wembley. Their role was to show Asante culture through drumming, dancing, weaving, carving, casting of brass objects and pottery.

British royals visited Asante and Asante royals visited Britain. In March 1977, Charles, Prince of Wales visited Kumasi and a durbar was held in his honour by Opoku Ware II at Manhyia Palace. At this durbar, the full panoply of Asante art was on display. When he became King Charles III, after the death of his mother Queen Elizabeth II in 2022, his coronation (similarly cast in art and ritual) was attended by Otumfuo Osei Tutu II and his wife Lady Julia.

3rd theme

The third theme is collaboration. Beginning with the art conversations between Osei Bonsu and Bowdich in the early 1800s to the present day, a range of actors have collaborated to showcase Asante art in its fullest intricate beauty and functionality, whether at home or abroad, whether held in legitimate or illegitimate hands.

The key actors include Asantehenes, their courtiers, researchers, funding agencies, educational institutions, museums, art foundations, mass media organisations, and governments. These actors have commissioned art, sold art, told the story of art and artefacts, tracked the journeys of the looted art of 1874, and finally – in recent times – worked together to bring home the objects.

In the final chapter, Agyeman-Duah presents a behind-the-scenes account of the negotiations between Asantehene Otumfuo Osei Tutu II and his representatives (including Agyeman-Duah) and officials of the British Museum and the V&A Museum that led to the selection and repatriation of the inaugural art objects. He also details negotiations leading to the return of seven objects gifted by the Wellcome Trust (from the private collection of its founder Sir Henry S. Wellcome) to the Fowler Musuem of University of California, Los Angeles.

One major lesson this final theme reveals is that while some governments have been consistently resistant to the idea of restitution, in its fullest sense, collaborators have worked around ideological, political and financial barriers to return these objects – permanently or temporarily – to their rightful owners.

There are several references to traditional cloth in the book: kente, adinkra, the three traditional funeral cloths – kuntunkuni, kobene and birisi. Just as the traditional one-piece cloth can be worn any number of ways, its design and patterns shifting as one’s body moves, you can read A History of Manhyia Palace Museum: Inaugural and other Objects in a number of ways.

You can read it as a straight forward history of the complicated relationship between the Asante empire and British colonial power. You can engage with it as a gallery of thought-provoking images that illustrate how art permeates many layers of Asante social life. You can read it as a lesson in how slowly the wheels of justice turn in the world of art restitution – in this case a hundred-year journey from the first unsuccessful appeal in 1924 by Asantehene Prempeh I to British officials for the return of stolen Asante royal artefacts.

Ivor Agyeman-Duah observes that 2024 marks a trinity of anniversaries in Asante cultural life: the 150th anniversary of the 1874 Sagrenti war, the centenary of the return of Prempeh I from exile in the Seychelles, and the silver jubilee of Otumfour Osei Tutu II. This is probably the best way to read A History of Manhyia Palace Museum: as a tribute to 150 years of the fierce and creative spirit of Asante people.