When bail becomes bondage: A jurisprudential reappraisal through the lens of the Paul Adom-Otchere case

In any constitutional democracy, bail exists not as a privilege granted at the whim of state actors but as a vital safeguard of the right to personal liberty. Yet, in Ghana today, bail, granted not by a court but by investigative bodies has increasingly morphed into a tool of coercion, often imposed in a manner that violates both the spirit and letter of our constitutional order.

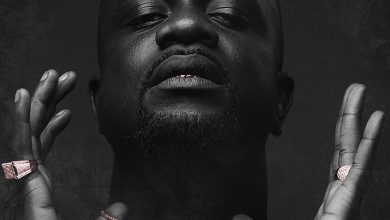

The case of Paul Adom-Otchere, a respected journalist and former Board Chairman of the Ghana Airports Company Limited, offers a sobering case study on the glaring absence of a statutory framework regulating the exercise of bail discretion in Ghana.

Paul was invited by the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP) over alleged procurement breaches. After co-operating fully with investigators and submitting to interrogation, he was granted bail but under a condition so palpably unreasonable that it bordered on farce. Paul was required to produce two landed properties registered in his name when in actual fact he had indicated in a questionnaire presented to him on arrival that he had no properties registered in his name.

The result? A constructive denial of bail, dressed up as compliance with due process. This development rekindles an important observation in Ghana’s criminal jurisprudence on when bail becomes a tool of oppression.

This incident is not merely anecdotal; it is symptomatic of a deeper structural malaise within Ghana’s criminal justice system: the lack of clear, binding legal standards for the grant, variation, and supervision of bail by investigative bodies. It is time to confront this lacuna not only for the sake of fairness, but for the development of our jurisprudence and the protection of liberty in a democratic society.

The 1992 Constitution is clear and uncompromising in its commitment to personal liberty. Article 14(1) affirms the right of every individual to freedom, while Article 19(2)(c) enshrines the presumption of innocence. Taken together, they establish that no one should suffer pretrial punishment, particularly when they have not been charged with any offence.

This principle was reasserted in the landmark decision of the Supreme Court in Martin Kpebu v. Attorney-General [2015], where the Court held that bail is a constitutional entitlement. It is therefore important that bail conditions are reasonable, necessary, and not so burdensome as to defeat the very right they purport to uphold.

By this logic, the bail condition imposed on Paul Adom-Otchere knowing full well that he could not meet it was not just harsh but the bail condition was used as a backdoor mechanism for detention, without judicial authorization.

The law presently offers no statutory guardrails to regulate the exercise of discretion by investigative agencies such as the OSP, EOCO, or the Police Service in the imposition of bail conditions. While Act 30 governs court-ordered bail, it is silent on the procedures, limitations, or safeguards applicable when investigative bodies issue bail administratively. This silence has allowed for discretion to operate inconsistently and, at times, oppressively.

In Paul’s case, there was no allegation that he was a flight risk, or that he posed any danger to the investigation. He had complied with the invitation, answered all questions, and was publicly traceable. On what basis, then, was such a restrictive condition imposed?

If someone of Paul’s stature, visible, respected, co-operative can be subjected to such disproportionate treatment, what happens to the unknown artisan, the market woman, the student, or the dissident with no public clout?

Paul’s case is not an isolated misjudgment as increasingly, politically exposed persons (PEPs), especially those in previous governments or persons affiliated with past administrations are subjected to punitive and sometimes theatrical bail terms meant to embarrass or humiliate them.

It is no coincidence that Kwabena Adu Boahen, a former Director of the National Signals Bureau and even his wife, found themselves facing bail conditions so severe they had to seek judicial variation. Nor is it lost on observers that Chairman Wontumi, a high-profile regional party chairman, was detained due to unrealistic bail demands. These individuals were not convicted. They were not even charged at the time. But they were, in effect, being punished through an untidy phenomenon increasingly used to “teach politicians a lesson.”

The right to bail is not a matter of privilege for the few. It is a constitutional guarantee for all. The case of Paul Adom-Otchere reveals what happens when that guarantee is left unprotected and unchecked. Our liberties become contingent on compliance with unreasonable demands, and the line between investigation and punishment begins to blur.

In Moti Ram v. State of M.P. (1978), the Supreme Court held that “bail should not be a device for indirect incarceration.”

If we truly believe in the rule of law, then we must insist on legal reform that restores balance and integrity to the pretrial process. It is time to end the era where bail becomes bondage to intimidate and punish. The growing pattern reflects not the strength of the law but the fragility of our legal protection and safeguards

Paul’s case has given me the rude awakening that where discretion is unchecked, abuse is inevitable.

I conclude with the profound saying of Montesquieu that “There is no greater tyranny than that which is perpetrated under the shield of the law and in the name of justice”

Nii Apatu-Plange Esq

(Apatu-Plange & Co PRUC)