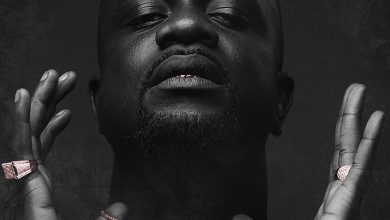

I’m ready to face GHAMRO in court – Akosua Adjepong

Highlife musician, Akosua Adjepong, has called the bluff of the Ghana Music Rights Organisation’s (GHAMRO) Interim Management Committee’s decision to file a lawsuit against her since it is not based on facts.

She pointed out that her assertion that the activities of the Interim Management Committee (IMC) were unlawful was not baseless but backed by facts, and she was prepared to present them whenever she was called upon to do so.

The Frema hitmaker had accused the IMC, with Rex Omar as Chairman, of operating illegally and demanded the Attorney General’s office shut it down.

Her tirades sparked outrage from some executive members of GHAMRO, who have threatened to sue her if she continued to spread false information.

A Board Member of GHAMRO, Mrs Diana Hopeson, disclosed in a recent interview with an Accra-based radio station, Rainbow Radio, that the organisation was making plans to take legal action against Akosua Adjepong for making what they regarded as false claims.

Akosua Adjepong, however, stated, in an interview with Graphic Showbiz on Monday, June 12, 2023, that she was unfazed by their ‘threats’ of a lawsuit, and she was prepared to face them off squarely.

“I am waiting for them, I don’t care at all if they want to sue me, I am very ready for them. If they think what I have been saying are lies, and they have their own truth somewhere, I am ever ready to face and confront them in court with facts,” she said.

She said she was convinced that GHAMRO’s threats of legal action were unfounded and were only intended to silence her, and it was something she was not ready to do.

“I’m not sure what I did wrong. What I do know is that people despise the truth, and if you tell the truth, you make enemies for yourself. They’re simply threatening to sue me to get me to stop talking, and I’m not ready to comply because I want what’s right to be done.

The Kokooko hitmaker disclosed to Graphic Showbiz that she was prepared to react to any counter-allegations made by GHAMRO.

She said some members had accused her of forming a spinners association and reaping profits, which had negatively impacted GHAMRO’s financial strength, claims she strongly refuted.

“They said I had established a spinners association, and I have been collecting money from them and issuing receipts. The truth will come out if I have or not. They claim I am saying things that are not true, but everything I am saying concerning them is from their annual report; the monies I mentioned are all coming from their annual report and it’s the truth.

“I feel it is now necessary for the public to be aware of whatever is happening, and I am prepared to present the facts. Everything I have said and will say is based on records that are now public, the annual report, etc. These are not made-up tales,” she added.

Akosua Adjepong added that she was not acting maliciously as some people were saying. but instead, her actions were intended to help shape the affairs of GHAMRO.

“Nothing I do is motivated by resentment or animosity; rather, I just want to make sure as an organisation, we uphold moral and legal standards,” she added.

Source: graphic online